Why testing conditional independence is so hard?

Conditional independence (CI) testing is widely used in causal discovery, scientific modeling, fairness, domain generalization, and robustness analysis. And yet it often fails in practice.

Why?

Let’s unpack the story.

Background

Before we talk about hardness, we need to understand what conditional independence really means — and how we try to measure it.

Conditional independence

At a high level, conditional independence between \(A\) and \(B\) given \(C\) asks:

Once we account for \(C\), does \(B\) still tell us anything about \(A\)?

Here are two concrete examples that help build intuition.

Example 1: fairness in lending

- \(A\) = loan decision

- \(B\) = race

- \(C\) = credit score, income

Race and loan decisions may be correlated marginally. But once we control for creditworthiness, race should no longer influence the decision. If it still does, the system may be unfair.

Example 2: distribution shift

- \(A\) = model prediction

- \(B\) = time of day

- \(C\) = true location

A model might use “time of day” as a shortcut for predicting location. If so, its predictions will fail when time distributions shift. If predictions remain independent of time once we condition on true location, the model is robust.

Formal definition

Conditional independence is defined as

\[A \perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad P_{A,B \mid C} = P_{A \mid C} P_{B \mid C}.\]Once \(C\) is fixed, knowing \(B\) provides no additional information about \(A\).

Equivalently, for almost every value of \(C\),

\[\text{Cov}(f(A), g(B) \mid C) = 0\]for all measurable functions \(f\) and \(g\).

In other words, conditional independence requires checking that no dependence remains between \(A\) and \(B\) at almost every value of \(C\).

CI as a hypothesis testing problem

In hypothesis testing, we consider two hypotheses:

- Null hypothesis (\(H_0\)): nothing interesting is happening.

- Alternative hypothesis (\(H_1\)): something is going on.

In CI testing, these become:

- \[H_0: A \perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C\]

- \[H_1: A \not\!\perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C\]

By default, we retain \(H_0\) and reject it only when the observed test statistic would be unlikely under the null.

In testing, two types of error can occur:

-

Type I error (false positive):

Rejecting \(H_0\) when conditional independence actually holds.

In CI testing, this means concluding that \(A\) and \(B\) are conditionally dependent when they are not. -

Type II error (false negative):

Failing to reject \(H_0\) when conditional dependence actually exists.

In CI testing, this means missing real conditional structure.

A good test aims to:

- Control Type I error at a predefined level \(\alpha\).

- Minimize Type II error (maximize power).

For many classical testing problems, this tradeoff is manageable, e.g., independence testing. But for conditional independence, however, controlling both errors simultaneously is much more difficult. We will see why in detail later.

Measuring conditional independence

A characterization of conditional independence is: \(A \perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C\) if and only if, for all square-integrable functions \(f \in L_A^2\), \(g \in L_B^2\), \(w \in L_C^2\),

\[\mathbb{E}_{C}\Big[ w(C) \, \mathbb{E}_{AB|C}\Big[ \big(f(A)- \mathbb{E}[f(A)|C]\big) \big(g(B)- \mathbb{E}[g(B)|C]\big) \Big] \Big] = 0.\]Intuition behind this CI measure:

- First, we remove the effect of \(C\) by considering the residuals

\(f(A) - \mathbb{E}[f(A)\mid C]\) and

\(g(B) - \mathbb{E}[g(B)\mid C],\)

which capture what remains unexplained by \(C\). - Then we measure the covariance between these residuals and weight it by \(w(C)\), allowing us to emphasize specific regions of the support of \(C\).

If any conditional covariance remains on a region of \(C\) with non-negligible probability, an appropriate \(w(C)\) will detect it.

RKHS view: from functions to operators

In principle, the condition involves all square-integrable functions, which is impossible to handle computationally.

Instead, we restrict the function class to a Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS), which provides a tractable and flexible approximation.

An RKHS \(\mathcal{H}_A\) contains functions that are linear w.r.t. \(\phi_A(a)\)

\[f(a) = \langle w, \phi_A(a) \rangle,\]where \(\phi_A\) is a feature map.

Define the conditional mean embedding

\[\mu_{A|C}(c) = \mathbb{E}[ \phi_A(A) \mid C = c ].\]It satisfies

\[\langle \mu_{A|C}(c), f \rangle_{\mathcal{H}_A} = \mathbb{E}[ f(A) \mid C = c ].\]So conditional expectations become inner products in Hilbert space.

We define the conditional cross-covariance operator

\[\mathcal{C}_{AB|C}(c) = \mathbb{E}_{AB|C}\Big[ \big(\phi_A(A)-\mu_{A|C}(c)\big) \otimes \big(\phi_B(B)-\mu_{B|C}(c)\big) \mid C=c \Big].\]This operator satisfies

\[\langle f \otimes g, \mathcal{C}_{AB|C}(c) \rangle = \text{Cov}(f(A), g(B) \mid C=c).\]So it encodes all conditional covariances.

The KCI operator

To aggregate over \(C\), we define

\[\mathcal{C}_{\text{KCI}} = \mathbb{E}_C\Big[ \mathcal{C}_{AB|C}(C) \otimes \phi_C(C) \Big].\]For any test functions \(f, g, w\),

\[\langle f \otimes g, \mathcal{C}_{\text{KCI}}\, w \rangle = \mathbb{E}_C\Big[ w(C) \, \mathbb{E}_{AB|C} \Big[ (f(A)-\mathbb{E}[f(A)|C]) (g(B)-\mathbb{E}[g(B)|C]) \Big] \Big].\]If the RKHSs \(\mathcal{H}_A, \mathcal{H}_B, \mathcal{H}_C\) are sufficiently rich (e.g., \(L^2\)-universal), then

\[\mathcal{C}_{\text{KCI}} = 0 \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad A \perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C.\]A common test statistic

So the problem reduces to estimating this operator from finite samples and determining whether it is zero.

Why CI testing is fundamentally hard

The binary embedding trick

We first explain why conditional independence testing is theoretically hard — regardless of which test or CI measure is used.

Start with any distribution of scalars \(A, B, C\) such that

\[A \not\perp B \mid C.\]So conditional dependence genuinely exists.

Now perform the following transformation.

- Sample scalars \(A, B, C\) where \(A \not\!\perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C\)

- Take binary expansions of \(A, B, C\).

- Truncate each to 100 bits: \(A_{100}, \quad B_{100}, \quad C_{100}.\)

- Embed \(A_{100}\) into \(C_{100}\) by concatenation.

- For example:

- \[C_{100} = 10011001\dots\]

- \[A_{100} = 10111100\dots\]

- The the new \(C\) is:

\(C_\text{new} = (C_{100} \text{ bits} || A_{100} \text{ bits}) = 10011001...10111100...\)

- For example:

- Finally, add an arbitrarily small continuous noise to all binary variables so the joint distribution remains absolutely continuous.

What just happened?

After this construction:

- \(A_{100}\) can be reconstructed from $C_\text{new}$$

- Therefore, once we condition on \(C_{\text{new}}\), \(B_{\text{new}}\) contains no additional information beyond what is already encoded in \(A_{\text{new}}\).

As a result,

\[A_\text{new} \perp\!\!\!\perp B_\text{new} \mid C_\text{new}.\]The conditional dependence has disappeared.

The insight here is:

Given any continuous distribution of \(A, B, C\), we can hide the dependence inside arbitrarily fine structure and construct a conditionally independent distribution that looks almost indistinguishable from the dependent one.

To detect this transformation, a test would need effectively infinite precision. Thus, no finite-sample test can reliably do this.

The Shah–Peters impossibility theorem

This construction is not just a clever trick. It reflects a deep structural limitation formalized by Shah and Peters (2020)

For any finite-sample conditional independence test, and for any alternative distribution where \(A \not\!\perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C\), there exists a null distribution (where \(A \perp\!\!\!\perp B \mid C\)) that the test cannot reliably distinguish from that alternative.

More concretely:

- If your test has power strictly greater than \(\alpha\) against some alternative,

- Then there must exist at least one null distribution under which the test’s Type I error exceeds \(\alpha\).

In other words, no CI test can be uniformly valid over all continuous distributions. If a test controls Type I error at level \(\alpha\) for all nulls, then it cannot achieves nontrivial power against all alternatives.

And this is not a shortcoming of some algorithm but rather a fundamental limitation of the problem itself.

Why it still fails in practice

You might think: these are adversarial constructions, surely in practice we don’t encounter them.

Yeah, we rarely face carefully engineered binary embedding tricks.

But… the mechanism behind the impossibility result is not artificial.

The core issue is:

Conditional dependence can live in fine-grained structure,

and detecting (in)dependence from finite samples is very delicate.

To see how this arises in a realistic setting, consider a problem inspired by engineering diagnostics:

Suppose we have high-dimensional vibration data \(C\) collected from a mechanical system.

We want to know whether the behavior of component \(A\) is connected to that of component \(B\), after conditioning on the vibration signal.

In many systems:

- The overall behavior of each component (predicting \(A\) or \(B\) from \(C\)) depends on broad, low-frequency trends in the vibration data.

- But any direct coupling between the two components may occur only through narrow, high-frequency resonances.

Detecting these two phenomena requires very different scales of analysis.

A Concrete Example

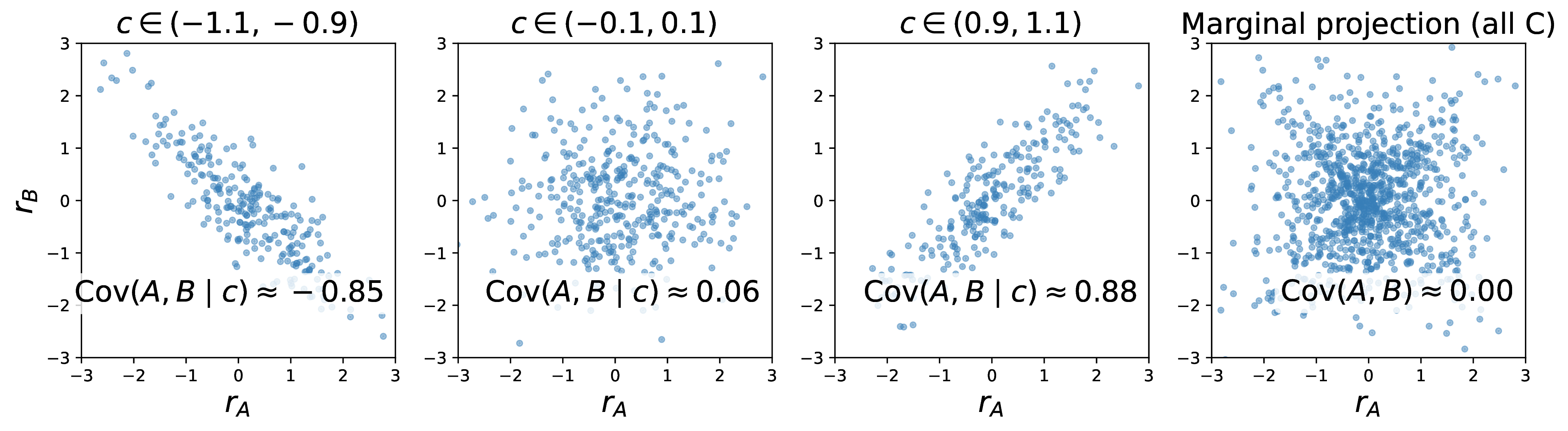

To formalize this, consider the model

\[A = f_A(C) + r_A\] \[B = f_B(C) + r_B\]where

\[(r_A, r_B) \mid C \sim \mathcal{N} \left( 0, \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \gamma(C) \\ \gamma(C) & 1 \end{pmatrix} \right).\]Here:

- \(f_A\) and \(f_B\) capture the systematic effect of \(C\).

- \(r_A\) and \(r_B\) represent unexplained noise.

- The only possible dependence between \(A\) and \(B\) comes from the residual correlation \(\gamma(C).\)

Now define:

- Under \(H_0\): \(\gamma(C) = 0\)

- Under \(H_1\): \(\gamma(C) = \sin(C)\)

So under the alternative, the residual correlation oscillates smoothly as a function of \(C\).

Why this is subtle?

The marginal residual correlation is

\[\mathbb{E}[\gamma(C)] = \mathbb{E}[\sin(C)].\]Since \(C \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) and \(\sin(\cdot)\) is symmetric,

\[\mathbb{E}[\sin(C)] = 0.\]So globally, the residual correlation averages out.

Marginally, there is no detectable correlation.

The dependence only appears locally in regions of \(C\).

This is the key difficulty:

Conditional dependence may oscillate, cancel globally, and only be visible at the right scale.

- If a test averages too aggressively over \(C\), it will miss this structure entirely.

- If it localizes too aggressively, estimates become very unstable and noisy.

Methods that only measure averaged conditional dependence can completely miss structured, localized interactions. For instance, the Generalized Covariance Measure (GCM), which effectively averages conditional covariance over \(C\), can fail when dependence oscillates and cancels globally

The tension discussed above already makes detecting subtle dependence fragile.

But there is an even deeper difficulty.

Even if we choose the right scale to detect dependence, CI testing can still fail — because of how we estimate conditional means.

If we look at the wrong structure, we may neglect real dependence and fail to detect it.

If the conditional means are estimated inaccurately, we may introduce artificial residual correlation and falsely conclude that dependence exists.

When conditional means are perfect

To understand where things go wrong in practice, let’s first look at the idealized setting — where we know the conditional means exactly.

When linear kernels are used for variables A and B, i.e., \(\phi_A(A)=A\) and \(\phi_B(B)=B\), the Kernel-based Conditional Independence (KCI) can be understood in three conceptual steps.

- Get the perfect conditional means: \(\mu_{A|C}(c) = \mathbb{E}[A \mid C=c], \qquad \mu_{B|C}(c) = \mathbb{E}[B \mid C=c].\)

- Form residuals by removing the effect of \(C\): \(R_A = A - \mu_{A|C}(C), \qquad R_B = B - \mu_{B|C}(C).\)

- Measure whether the residuals are still dependent, using a kernel on \(C\) to localize the comparison across different regions of the conditioning variable.

Intuitively, KCI asks: after removing everything that can be explained by \(C\), is there any remaining dependence between \(A\) and \(B\)?

In this ideal infinite-sample regime, where the conditional means are known perfectly:

-

Under \(H_0\), \(\text{Cov}(R_A, R_B \mid C) = 0\) almost surely, so the KCI statistic converges to zero.

-

Under \(H_1\), residual dependence remains for some values of \(C\), and the kernel aggregation detects it.

In this idealized setting:

- Type I error is controlled, because under the null the population statistic is exactly zero.

- Type II error depends only on how subtle the remaining dependence is, and whether the chosen kernel can resolve the relevant structure.

In other words, if the conditional means were known exactly, CI testing would be a well-behaved problem.

The real trouble begins when we have to estimate those conditional means from data.

When we have to estimate the conditional means

Everything above assumed we knew the true conditional means.

In practice, we do not.

We estimate them from data, typically using kernel ridge regression

Write the estimators as

\[\hat{\mu}_{A|C}(c) = \mu_{A|C}(c) + \delta_{A|C}(c),\] \[\hat{\mu}_{B|C}(c) = \mu_{B|C}(c) + \delta_{B|C}(c),\]where \(\delta_{A\mid C}\) and \(\delta_{B\mid C}\) are the regression errors.

What happens to the residuals?

The empirical residuals are now

\[\hat{R}_A = A - \hat{\mu}_{A|C}(C), \qquad \hat{R}_B = B - \hat{\mu}_{B|C}(C).\]Substituting,

\[\hat{R}_A = (A - \mu_{A|C}(C)) - \delta_{A|C}(C),\] \[\hat{R}_B = (B - \mu_{B|C}(C)) - \delta_{B|C}(C).\]Under our generative model,

\[A - \mu_{A|C}(C) = r_A, \qquad B - \mu_{B|C}(C) = r_B.\]So

\[\hat{R}_A = r_A - \delta_{A|C}(C), \qquad \hat{R}_B = r_B - \delta_{B|C}(C).\]Now multiply:

\[\hat{R}_A \hat{R}_B = r_A r_B - r_A \delta_{B|C}(C) - r_B \delta_{A|C}(C) + \delta_{A|C}(C)\delta_{B|C}(C).\]Taking conditional expectation given \(C\) (and assuming regression is trained on independent data so errors are fixed w.r.t. test sample),

\[\mathbb{E}[\hat{R}_A \hat{R}_B \mid C] = \mathbb{E}[r_A r_B \mid C] + \delta_{A|C}(C)\delta_{B|C}(C).\]But

\[\mathbb{E}[r_A r_B \mid C] = \gamma(C).\]So we obtain

\[\mathbb{E}[\hat{R}_A \hat{R}_B \mid C] = \gamma(C) + \delta_{A|C}(C)\delta_{B|C}(C).\]Under \(H_0\), \(\gamma(C) = 0.\) So the population residual covariance becomes

\[\mathbb{E}[\hat{R}_A \hat{R}_B \mid C] = \delta_{A\mid C}(C)\delta_{B\mid C}(C).\]Even though \(A \perp B \mid C\) holds in truth.

When KCI aggregates over \(C\) using the kernel,

\[\text{KCI} = \mathbb{E} \left[ k_C(C,C') \, \delta_{A\mid C}(C) \delta_{A\mid C}(C') \delta_{B\mid C}(C) \delta_{B\mid C}(C') \right].\]So the regression errors induce a nonzero population statistic which leads to inflated Type I error.

This is not sampling noise.

It is structural bias introduced by imperfect regression.

Type I error inflation and type I/II tradeoff

Why type I error explodes

Under ideal conditions (perfect regression), the KCI statistic behaves like a degenerate U-statistic under the null.

Because the population statistic is exactly zero under \(H_0\), the first-order term of the U-statistic vanishes. This degeneracy forces the variance to decay at rate \(1/n\).

Null approximations — whether chi-square mixtures, Gamma approximations, or wild bootstrap — rely critically on this structure.

They assume:

- The population mean under \(H_0\) is zero.

- The statistic is asymptotically centered.

- The dominant stochastic fluctuation is of order \(1/n\) around zero.

When conditional means are estimated imperfectly.

Under \(H_0\), the statistic no longer has zero population mean:

Because once the statistic has nonzero mean, the U-statistic is no longer degenerate. Its leading term behaves like an empirical average of nonzero quantities.

Formally:

- The bias term does not vanish with \(n\).

- The centered fluctuations around this bias are of order \(1/\sqrt{n}\).

So instead of shrinking toward zero, the statistic concentrates around a positive constant:

\[\text{KCI}_n = \text{Bias} + O_p(1/\sqrt{n}).\]Unless the regression error itself shrinks sufficiently fast, the bias remains.

| Case | Mean of KCI | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|

| Perfect regression | 0 | \(O(1/n)\) |

| Imperfect regression | \(O(1)\) | \(O(1/\sqrt{n})\) |

The consequence:

Null calibration procedures still assume a centered statistic.

But the true distribution is shifted.

As test sample size \(n\) grows:

- The variance shrinks.

- The bias does not.

Eventually, the statistic will almost surely exceed any fixed null threshold.

Type I error thus inflate with increasing \(n\).

This is why regression error is not a small nuisance.

It fundamentally changes the asymptotic regime.

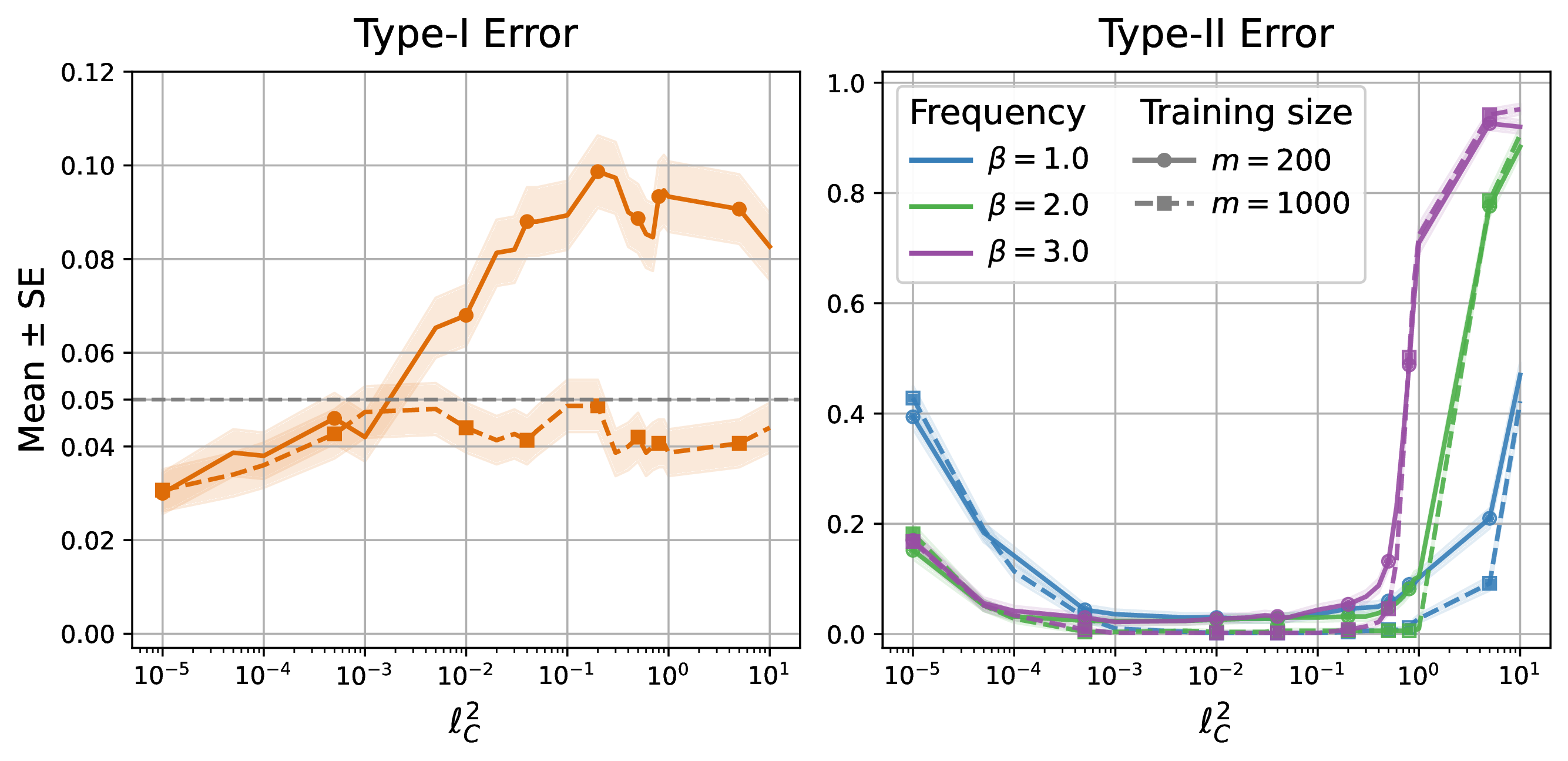

Type I and type II error tradeoff

In principle, we choose the kernel (especially the bandwidth on \(C\)) to maximize power — that is, to better detect conditional dependence. However,

The same kernel choice that amplifies true dependence can also amplify regression-induced bias.

Recall that under imperfect regression, the null statistic contains the term

\[\delta_{A\mid C}(C)\,\delta_{B\mid C}(C).\]These regression errors are not arbitrary noise. They are smooth, structured functions of \(C\).

When we optimize the kernel bandwidth to increase sensitivity to dependence, we are effectively choosing a weighting function over \(C\).

If that weighting aligns with regions where \(\delta_{A\mid C}(C)\,\delta_{B\mid C}(C)\) is large, the test statistic increases — even under the null.

In other words:

- When we tune the kernel to detect real structure,

- We may instead be tuning it to highlight structured regression error.

This creates a fundamental tradeoff:

- A wider kernel smooths aggressively → lower Type I error, but reduced power.

- A narrower kernel localizes aggressively → lower Type II error, but increased risk of Type I inflation.

Optimizing for power can therefore push us directly into spurious rejection.

Conditional independence testing is fragile not only because dependence may be subtle,

but because the very act of searching for it can create it.

The central lesson

CI testing does not merely require detecting dependence. It also requires estimating conditional means accurately enough.

That is a very strong requirement.

And that is why CI testing fails in practice.

Final Summary

Takeaways: why CI is hard both theoretically and practically

Conditional independence testing is difficult for structural reasons:

-

Dependence can hide in subtle structure.

Conditional dependence may be localized, oscillatory, or globally canceling — detectable only at the right scale. -

Regression error induces spurious dependence.

Imperfect estimation of \(\mathbb{E}[\phi_A(A) \mid C]\) and \(\mathbb{E}[\phi_B(B) \mid C]\) introduces artificial residual correlation, even under the null. -

Detection is unstable in both directions.

Conditional dependence is not only hard to detect (high Type II error), it is also easy to hallucinate when conditional means are estimated inaccurately (inflated Type I error).

Moreover, these phenomena are not specific to KCI. They arise in essentially all conditional dependence measures that rely on estimating conditional expectations, and aggregate residual covariances across values of \(C\).

Practical recommendations:

Though the theory is pessimistic, CI testing can still be useful in practice — if we treat it as a fragile procedure and design the pipeline accordingly.

-

Sample splitting.

Use an independent training set to estimate the conditional means \(\hat{\mu}_{A|C}\) and \(\hat{\mu}_{B|C}\), and a separate test set to compute the KCI statistic and calibrate the null.

As a rule of thumb, the training set should be at least as large as the test set, and preferably much larger (how much larger depends on the complexity of \(\mathbb{E}[A|C]\) and \(\mathbb{E}[B|C]\)). -

Strong regression (bias matters more than you think).

Use flexible, low-bias regression models for conditional mean estimation. CI testing is extremely sensitive to systematic regression error: even small structured bias can look like conditional dependence under \(H_0\). -

Kernel choice for power (but only on the training split).

If you tune the conditioning kernel \(k_C\) (e.g., its bandwidth) to improve power, do it using only the training split—e.g., by maximizing an estimated signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Then freeze the choice and evaluate on the test split. -

Be cautious about “discoveries.”

Even with all safeguards, it is still easy to trick yourself: power tuning can overfit to regression artifacts, and null calibration can silently fail when regression error does not decay fast enough. Treat borderline rejections with skepticism and stress-test them with sensitivity checks.

Citation

If you find this blog helpful, please consider cite

@inproceedings{hehardness2025,

title={On the Hardness of Conditional Independence Testing In Practice},

author={He, Zheng and Pogodin, Roman and Li, Yazhe and Deka, Namrata and Gretton, Arthur and Sutherland, Danica J},

booktitle={The Thirty-ninth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems},

year={2025}

}

Paper: On the Hardness of Conditional Independence Testing In Practice